This document is also available in: text or Word formats.

Vizard-Mask-art - 10/10/15

"Vizard Paper Mache Mask - Intended Setting: Nobility, court and social use" by Mistress Milesenda de Bourges, OL.

NOTE: See also the files: Masques-Masks-art, masque-msg, theater-msg, linen-msg, cotton-msg, glues-msg, velvet-msg.

************************************************************************

NOTICE -

This article was added to this set of files, called Stefan's Florilegium, with the permission of the author.

These files are available on the Internet at: http://www.florilegium.org

Copyright to the contents of this file remains with the author or translator.

While the author will likely give permission for this work to be reprinted in SCA type publications, please check with the author first or check for any permissions granted at the end of this file.

Thank you,

Mark S. Harris...AKA:..Stefan li Rous

stefan at florilegium.org

************************************************************************

Vizard Paper Mache Mask

-

Intended Setting: Nobility, court and social use

by Mistress Milesenda de Bourges, OL

(2013 Village Faire Regional Art Sci, Baronial Champion, 2014 Kingdom Art Sci merit)

Contents

Summary of Submission

Historical Reference for Submission

Style and Style Choices:

Materials: Discussion of material substitutions

Materials: Clay

Materials: Plaster of Paris

Materials: Cartapesta

Cartapesta Materials: Laid Cotton Rag Paper

Cartapesta Materials: Wheat Paste

Materials: Linen

Materials: Cotton Velveteen

Materials: Cotton Thread

Materials: Glass

Materials: Hide Glue

Process (including period relevance and reflection)

Resources

Summary of Submission

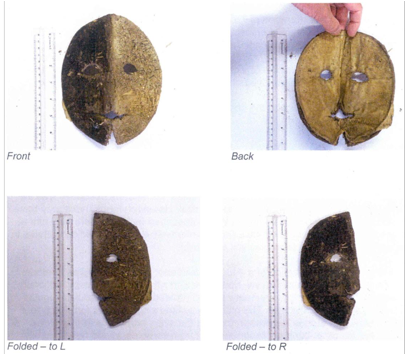

This submission is comprised of one vizard style mask, constructed with period cartapesta technique (modernly known as paper mache in English.) The mask has been hand constructed from period materials with three separate layers: an inner cardboard core, an outer covering of velvet, and an inner lining of linen. This piece is based off a surviving extant mask, known as the Daventry Mask, found stowed inside the walls of a house, originating from the mid 1500's in England.

Figure 1: Daventry Mask (extant)

Historical Reference for Submission

Masks were a popular and omnipresent part of medieval life, ranging from use in theater and mystery plays as costuming, to a more social and political role in the Italian city states. In Venice, the use of masks was a common every-day practice, allowing citizens to hide rank and identity to speak freely or engage in any desired activity. Mask making there fell under the purviews of the conglomerate of scribes and painters, with smaller groups forming within the larger guild (Datta). By 1436, mask use was popular enough for the Mascareri (or mask makers) to have their own guild ("Mascareri). Masks in England were less common place but the concept of the vizard mask was popular in the mid-1500s, with documentable presence in 1558 of the word being used in reference to a mask.

A great many of the Daventry mask's materials were popular or commonly found in Italy, an unsurprising connection given the popularly of using masks in Italy and the mask maker's craft at full height there. In Italy, this mask was called a Moreta, and was used for a purpose of concealing the face from identification as well as protection from the sun (Tieuli). The influence of expanded trade routes with Italy during this time period can be easily seen in the Daventry Mask's materials and construction, as well as the style.

The vizard mask was popular for female theater-goers in the sixteenth century in England, presumably to maintain dignity at the theater, but had fallen largely out of use by the mid 1600's. Other sources indicate that it was used to protect the complexion during outings. The Diaries of Pepys, written starting in 1633 indicate that the vizard was still in fashion during his time period. In 1583, Phillip Stubbes wrote in Anatomie of Abuses regarding encountering English ladies in these vizard, or invisory, masks.

"When they use to ride abrod, they have invisories, or masks, visors made of velvet, wherwith they cover all their faces, having holes made in them against their eyes, whereout they look. So that if a man, that knew not their guise before, should chaunce to meet one of them, he would think hee met a monster or a devil; for face hee can see none, but two brode holes against her eyes with glasses in them."

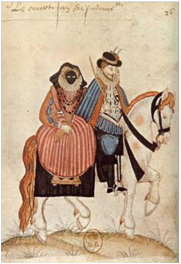

Figure 1 as follows is a 1581 illumination showing a horseman and his wife, who wears a vizard style mask. Figure 2 references a woodcut of an Elizabethan lady, also wearing a vizard style mask. The mask style became so fashionably popular that it can even be seen in miniature as in the extant doll mask shown in Figure 3 and 4 which, while out of period, illustrates the procession of the fashion through the 1600s.

Figure 2: "A horseman with his wife riding behind him," 1581.

Figure 3: "In this fashion noble women either ride or walk up and down. " Omnium Poene Gentium Habitus 1581

Figure 4 and 5: Lady Clapham's Doll's Vizard Mask, 1680

Style and Style Choices:

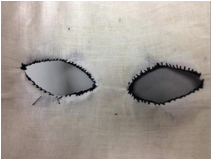

Vizard masks are seen in a variety of styles in drawings and in the extant piece. Discussion of material aspects aside, choosing the precise style was a matter of combining technique plus style elements. While the Daventry extant piece as well as the Lady Clapham out-of-period doll's mask show small eye holes and a split chin, I have chosen instead to make slightly larger eye holes in my reproduction in order to suit a wider variety of face shapes and eye-spacings; the Elizabethan lady would have likely had one fit to her face to ensure proper fit and shape.

Similarly, I chose a closed chin style, closer to the illumination and woodcut images that were found. This style better suited the molding process and, looking at the extant and the doll's mask, I remained uncertain if the chin "split" was intentional or a product of wear and flattening over time as the curvature of the bottom of the mask would place stress upon this point.

Lastly, the measurements of my mask exceed the original mask's measurements of 195mm in length and 170mm in width. I wished my mask to fit properly and the smaller size was not conducive to modern proportions or sizes for wearing.

Materials: Discussion of material substitutions

The only material substitution from the original piece was made in the inclusion of linen for a lining rather than silk. I did not have any sufficiently bodied silk to line the mask with that would have maintained any sort of comfort enhancing or absorbency properties; my available silk was all 12mm china silk whereas a raw silk would have provided more body and comfort as a lining. Further, this thin "china" silk allowed the inner hide glue, which helped secure the lining, to show through.

Linen was substituted as an alternative period choice for the lining, offering a thicker, more absorbent and comfortable fabric.

Materials: Clay

Clay was readily available throughout Italy and England during this time. A mixture of clay-dirt particles and water, clay is typically moist and found around the areas of rivers or streams and can be easily dug from these areas for use. Cennini and Theophilus both reference the use of clay for sculpting and molds.

"On the same subject. You may also cast your own person, as follows. Get ready a quantity of plaster or of clay, well worked over and clean, wet up quite soft, as if it were an ointment; and have it spread out on a good broad table, such as a dining table. Have it placed on the ground; have this plaster or clay spread out on it a foot deep. Fling yourself on it, on whatever side you wish, front or back or side." (Cennini 129)

The clay that I chose to use was an earth based, natural clay. Given the sandy nature of Florida's soil, I chose to purchase my clay rather than attempt to find local, natural clay that would work. This would not have been an issue in England or in Italy for mask-making.

Figure 6: Earth clay

Materials: Plaster of Paris

Plaster of Paris, or gypsum plaster, was available in period and is referenced by Cennini.

"Have some plaster of Paris ready, made and roasted, fresh and well sifted. Have some tepid water near you in a basin, and put some of this plaster briskly on top of this water. Work swiftly, for it sets fast; and do not get it either too liquid or not enough so." (Cennini 126)

Gypsum was most readily available from quarries around Montmartre (thus Plaster of "Paris") but was available in other areas as well and is found widely throughout Europe in period. Its soft nature and the ready way in which it returned to hardness upon being mixed with water lent it readily to casting and mold making.

I purchased my plaster of paris at the local hardware store, a practice that would have also been used in period as artisans would have purchased the ground gypsum and knew it as a readily available plaster compound.

Materials: Cartapesta

In researching the

museum files for the Daventry Mask, it was indicated that the core was made

from cardboard.

Pasteboard was in common use from the fifteen century onward, as seen in covers of manuscripts in the Shoenberg library at Pennsylvania State, which contains several manuscripts with pasteboard covers from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Card board and card stock, in period, were made from layers of paper adhered together with glue, rather than a pressed thicker piece of paper or the corrugated card board of our time. The technique, in relation to masks and in Italian, is referred to as cartapesta – what we would modernly and in English refer to as paper mache. I found several references to period cartapesta and a modern recipe which was a replica of the materials I had used to make my pasteboard for a previous project. This leant credence to the wheat paste and paper recipe I was using for this mask project.

Cartapesta Materials: Laid Cotton Rag Paper

I used Fabriano CMF Ingres laid paper in natural color, at a 90 gram weight. The sheets were large and needed to be torn into pieces for use in the mask's cartapesta base.

Paper in period was made from fibers – usually linen or cotton – shredded and beaten into a pulp, strained, and pressed into a screen. This "rag paper" was likely made from fabric scraps. Called "laid paper" it was most prevalent in western Europe in this period. Laid paper can have a very thick texture or very thin, dependent on the manner in which the paper is made. For papers requiring a smoother finish, laid paper could be burnished with a stone for better finish.

A mask maker most certainly would have purchased their paper, as paper making was an entirely separate occupation, and the manufacture would have had guild protection.

Figure 7: Mold screens used for sifting fibers out of water baths to make into sheets of paper (Paperwright).

Cartapesta Materials: Wheat Paste

Wheat paste was a common adhesive for period book binders. Since hardened paper mache or cartapesta is similar to the paste board that would have been used for book covers and other thicker "card board" papers, I chose to use wheat paste to bind together the layers of my cartapesta in the mask. This paste is also similar to the starch glues that Italian mask makers still use.

Wheat paste has the benefit of stiffening paper due to starch. Useful in conservation, this is also an excellent choice for a mask form that needs to have some stiffness to it.

I used a recipe contributed by Master RanthulfR of the Middle Kingdom, After consultation with several individuals, direct recipes for "blue collar" work are not often found. Cennini references the use of wheat glue in his treatise but not a precise recipe with measurements.

"Take a pipkin almost full of clear water; get it quite hot. When it is about to boil, take some well-sifted flour; put it into the pipkin little by little, stirring constantly with a stick or spoon. Let it boil, and do not get it too thick. Take it out; put it into a porringer." (Cennini 65)

Master Ranthulf R suggested one part unbleached flour sifted into three parts cold water, stirred to eliminate lumps and then slowly heated on the stove while stirring constantly. When the paste started to get thick and burped and bubbled, it was done and could be removed. I chose to use unbleached wheat flour, with assurance that finely ground flour would have been readily available in Europe in the 1500's. The remainder of the wheat paste was kept in the refrigerator for better storage until I was certain I no longer needed it.

Figure 8: Sifted flour and water being stirred on the stove

Figure 9: Paste starting to thicken

Figure 10: Completed wheat paste in storage container

Materials: Linen

The inner lining of the mask is made from lightweight linen (about 3.5 ounces per yard). This natural material was used in period and is substituted for a heavy weight silk lining as seen in the original mask.

Linen was seen throughout the 1500's and was even recorded as part of the expenditures for the Queen's household. "Linen varied in quality and in price, depending on its end-use and the wealth of the prospective buyer," and was woven in most European countries by the sixteen century (Arnold 5). Italian linen was finely woven and – coupled with the region's propensity for masks –makes a linen and mask pairing comprehensible. Additionally, the fabric was typically used for garments worn close to the skin due to its cooling properties and ability to wick and absorb moisture, making at an ideal liner. Due to the lack of waste which typically had every scrap and piece of fabric used, it would make sense that a smaller piece could be used for something such as a mask lining, particularly – as this item is for a noble patron – if the linen were of higher quality.

Materials: Cotton Velveteen

This material was chosen to replicate the pile and feel of period velvet, which seems to have had a generally lower pile than what is termed "silk velvet" today. In period, velvet was made of silk thread woven through a backing, with loops of thread pulled up and over rods as part of the weaving process and cut down to create the velvet's pile. The process of making velvet today is much the same, though machines have simplified and made the process speedier and more affordable. Weaving silk velvet was particularly popular throughout Italy and in Spain in the 1400's and 1500's, where the silk trade had a tremendous economical impact and where many fabulous patterns of cut velvet were produced (Watts). Again, we can see a connection to the Italian mask makers here and a ready connection of materials to the English observer "replicating" an Italian form. The presence of any velvet on the extant mask certainly labels it as a noble-woman's accessory as only the wealthy could afford such fabric.

Silk velvet today is costly, which was a prohibition for me in this case, but also tends to be a slightly higher pile while the mask covering required a low-pile velvet. Cotton velveteen was chosen for this reason. As spinning and weaving were a separate profession, it would have been appropriate to buy this fabric in period, as I did for this project.

(Please see: Materials, Cotton Thread for additional information on cotton)

Materials: Cotton Thread

Like many other materials in the Daventry mask, cotton thread was a commonly available item in the sixteenth century in England, particularly via the trade routes to Italy where cotton was routinely imported from the middle east and India. Milanese records indicate a cost of about 12 dinari per .66 pounds of cotton yarn, produced in the mid-1500s, with evidence of international trade (Mazzaoui). Guilds, in fact, regulated the production of cotton thread and fabric in the city-states and the fabric and material were used widely both in Italy and with other nations which also grew and produced cotton thread and fabric. By the sixteenth century, cotton was becoming more readily available but it seems to have still been a trade commodity primarily brought in from other areas into England ("Cotton").

The Daventry mask was stitched with cotton thread which was again used here. My thread was purchased, as it would have been in period as spinning and weaving were a separate guild or profession from mask making. I chose a black thread for the whip stitch around the edge, and white thread, as was found attaching the interior bead.

Materials: Glass Bead

Glass beads were found back through antiquity and in Greek and Roman times. By the 1500's, when the Daventry mask was created, they were a common embellishment and trade item. Beads were formed by heating or melting glass into shape or by carving natural products into shape. Given the structure and glass materials, this bead was likely hand made. Glass production of many sorts was popular throughout Italy and many other European nations, making this a common product.

The bead found on the Daventry mask is a non-descript black, round bead of approximately 10mm in size. I found a similar black glass 10mm bead, via purchase, and used it for my mask.

Figure 11: Bead from original Daventry mask

Materials: Hide Glue

Hide glue is glue derived from the boiling of parchment and vellum and skin scraps. This smelly process releases the proteins in the animal skin and creates a thick, viscous and sticky glue suitable for glue paper but also fabrics and wood.

"There is a glue which is known as leaf glue; this is made out of clippings of goats' muzzles, feet, sinews, and many clippings of skins. ... This glue is used by painters, by saddlers, and by ever so many masters, as I shall show you later on. And it is a good glue for wood, and for many things." (Cennini 67)

I used purchased hide glue from Guild Mirandola, rather than boil my own hide pieces as I did not have sufficient hide scraps to process on my own.

Process (including period relevance and reflection)

False start: My initial attempt at this project was what I term a "spectacular failure." I originally tried to do a half mask as a tester, however, the clay form itself wasn't what I wanted for a result and the plaster of paris mold was too thin and broke when I tried to empty the mold of clay.

From this I learned firstly that I needed to balance my clay sculpture more carefully and even out the features. Secondly, I learned that I needed to make a thicker plaster of paris mixture for the mold.

Figure 12: Original sculpted mask with clay trench for mold

Figure 13: Mask covered in thin plaster of paris

Venetian and cartapesta mask making has changed very little in the centuries. Clay sculptures, paper mache, and plaster molds are all still used as they were centuries ago ("Venetian Masks"). Before starting, I watched a video from a current Italian mask maker on the traditional methods he used in order to help affirm my technique.

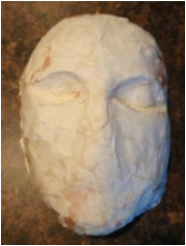

To begin with I needed to sculpt a base that would be cast in plaster for a mold for the mask. Looking at the techniques of mask makers today, this is the first step for creating masks in the traditional method. (Boldrin).

I used clay to sculpt the mask by hand, using water to smooth the form. I used another mask base that I knew fit my face for reference but did not use this as a mold or support but only for appropriate sizing and proportion.

The trickiest part of sculpting was getting the features balanced. I compensated for this by often turning the sculpture upside down as then irregularities are more visible to the eye.

Figure 14 Sculpted vizard base next to model form

Once the sculpture was completed, I laid it on plastic to avoid any accidents while pouring. The mask was "trenched" with clay, allowing for a place the plaster of paris could collect and build up around the mask without running off. This technique was gleaned from watching videos of several Italian mask makers who carry on traditional techniques today.

Figure 15: The mask with clay trench around it prior to pouring

Figure 16: Mixing plaster of Paris with water

Once the clay sculpture was completed, I began to mix the plaster of paris. Plaster of paris was also used in period for casting. Cennini specifically references it for casting life models. Once the mixture was stirred and oatmeal like in consistency, I poured it over the clay mask to let it dry. "Take some of this preparation [the plaster] and put it on and fill in around the face with it," Cennini states in reference to casting a face (126). The trench worked well, holding the plaster of paris in place.

I let the plaster of paris cure overnight to ensure that it was thoroughly dry and sturdy and then flipped the mold over and scooped out the clay mask form. The clay was discarded.

Figure 17: Plaster mold completed

Figure 18: Bumps in mold shaved out

I next inspected the mold for any irregularities. There were one or two small bumps where lumps had formed in the plaster. I shaved these out with a sharp knife to get the smoothest possible mold.

The next step was to prepare my wheat paste mixture which would serve as an adhesive for my cartapesta layers. Please see: Materials: Wheat Paste for more information on this process.

Once the paste was finished, I spent some time preparing the laid paper for use. The pieces needed to be small – a few inches square at most – and could have no hard edges that would inhibit smooth layering. I prepared a pile of these paper pieces before beginning so that I would have plenty to work with. It is possible, in period, that remnants and scraps were used for this portion of the mask as the expense of paper simply to be shredded in this manner seems extreme. Since this paper was remnant from my tarot card project, this was a good correlation.

Figure 19: prepared wheat paste

Figure 20: Prepared paper pieces

With the paste and paper prepared, I began layering paper into the mold. Cennini states to use a light oil against the surface of the face when life casting to work as a release agent; "Take rose-scented, perfumed oil; anoint the face with a good sized minever brush," (124). I used a light coating of olive oil – readily available in period – on the plaster of Paris mold to prevent the first layer from sticking. As plaster of paris is porous, I had to stop to coat the mold as I went or the oil would completely absorb by the time I reached a new portion of the mask. F

Figure 21: Olive oil for release agent and layering the first layer of paper.

At this point, I paused to make a sample card so I could see how many layers I would need. Since this paper was particularly thick, I tested six layers first, but decided the mask was still a bit too thin at that point. At eight layers, I felt the test sample had sufficient thickness and stiffness to be sturdy. Subsequent layers of paper did not require the olive oil release as they needed to adhere to one another. I alternated directions (horizontal and vertical) as I layered the remaining layers into the mold so I could see which layer I was on and what areas I had already covered in that particular layer.

Figure 22: Mold layered with paper

Once the cartapesta layers were complete, I left the mask to dry for forty-eight hours, checking it for dryness during this time. After 48 hours it became apparent that the mask was not going to fully dry in the mold – something I had not anticipated. The interior layer was quite hard but the rest remained flexible. At this point, I carefully pried the mask out of the mold with my hands, smoothed out a few bent portions, and left the mask to continue drying. The interior dry layer provided stability for the design while the rest of the moisture evaporated.

Figure 23: Mask removed from mold and drying

I let the mask sit for another day until dry. I applied one last layer of cartapesta to the top of the mask to provide as smooth a surface as possible and a more finished feel.

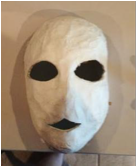

The mask now needed to be trimmed. The mold had caused some irregularities in the edges and the eye-holes required evening. The original extant piece also had a "mouth" hole that needed to be carved; this was, ironically, more likely to be for letting air into the mask for breathing rather than speaking as the mask would be secured by a bead held in the teeth. Without this hole, however, the mask would be unbearably stuffy and difficult to breathe in. I sketched my trim lines with charcoal and then used a sharp knife to even the edges, trim out the eye holes, and incise the mouth hole.

Figure 24: Marked with charcoal prior to trimming

Figure 25: trimmed and with eye and mouth holes cut

At this point, were I making a carnival or painted mask, I would have applied several layers of gesso to the surface of the mask for superior painting, however the Daventry Mask was covered in fabric.

I applied the cotton velvet first, applying a thin layer of hide glue to secure the fabric in place and then stretching it taught and trimming with enough room to stitch the fabric after. Slits were cut over the eye holes and mouth hole for later stitching there.

Figure 26: Mask with velvet applied

Figure 27: Interior with hide glue applied

Next, the mask was flipped over and a thin layer of hide glue was applied to the inside. I had to be careful to keep this layer particularly thin due to the thin nature of linen. I mopped up a few spots where pooling occurred with scrap fabric.

Once the glue was applied, I smoothed in a piece of linen for the lining and repeated cutting slits for the eyes and mouth as I had done with the cotton.

Figure 28: Interior with linen lining applied

I trimmed down the linen lining and began stitching around the edge of the mask to secure the fabric layers to one another. Close inspection of the edges of the extant mask indicated the presence of a whip stitch used to secure most the edges. This was a period stitch used in the 1500's and prior and was sturdy and relatively easy to replicate. I am not a seamstress of any great ability and so I focused on keeping my stitches small, close together, and pulling the fabric as evenly as possible. The curve of the mask sometimes made the fabric pucker but this did not distort the overall smoothness or look of the piece. I also whip stitched the interior eye holes and mouth hole.

Figure 29: Whip stitching around the eyes

Figure 30: Whip stitching the mouth hole, in process

I then used white cotton thread to sew the black bead into the interior of the mask just above the mouth hole. I used a knot to secure the thread through the bead and then left enough slack in the cotton thread to allow the mask to be held up by the bead being placed between the teeth. A second knot secured the thread to the mask lining.

Figure 31: Bead attached to mask

Figure 32 and 33: Completed mask exterior and interior

Resources

"A horseman with his wife in the saddle behind him," Habits de France. 1581. Fashioning the Early Modern Era. http://www.fashioningtheearlymodern.ac.uk/object-in-focus/visard-mask/ Date accessed: 16 September 2013.

"An Amazing Find of an Elizabethan "Vizard" Mask." Fashioning the Early Modern Era. http://www.fashioningtheearlymodern.ac.uk/object-in-focus/visard-mask/ Date accessed: 16 September 2013.

Arnold, Janet. Patters of Fashion 4: The cut and construction of linen shirts, smocks, neckwear, headwear, and accessories for men and women c 1540-1660. New York: Macmillan, 2008.

Asplund, Randy. "Wheat Paste." Email. 8 Oct. 2012.

Baker, Cathy, Dan Clement, Deborah Mayer, Denise, Thomas, Doris Hamburg, Francis Prichett, Frank Mowery, Janet Ruggles, Jill Sterrett, John Krill, Katherine Eirk, Lage

Carlson, Lynne Gilliland, Martha M. Smith, Mary Baker, Paula Volent, T.K. McClintock, Tim Vitale. Authors. "Adhesives." American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. Web. 23 12 Jan. 2012. 23 Dec 2012. < http://www.conservation-wiki.com/w/index.php?title=BP_Chapter_46_- _Adhesives#46.3_Materials_and_Equipment>

Boldrin, Sergio. Massamino Boldrin. La Botega de Mascareri. "How we create masks." Video. http://www.mascarer.com/index2_en.html Date accessed: 16 September 2013.

"Bookplate of Pietro Ginori Conti." Schoenberg Collection. Web. 12 Dec 2012. http://sceti.library.upenn.edu/sceti/ljs/PageLevel/index.cfm?option=view&;ManID=ljs379 Date accessed: 17 September 2013.

Canavese, Carlos. "Pegamento para cartapesta." Teatro Tecnico. http://www.teatro.meti2.com.ar/tecnica/escenariografia/practica/papelycola/cartapesta/cartapesta 1/cartapesta1.htm Date accessed: 16 September 2013.

Cennini, Cennino D'Andrea. Il Libro Dell'Arte. Trans. Daniel V. Thompson Jr. New York: Dover Publications, 1960. Print.

'Cotton - Cotton yarn', Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1550-1820 (2007). http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=58731 Date accessed: 17 September 2013

Datta, Satya. Women and men in early modern Venice: Reassessing history. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2003. Accessed online.

http://books.google.com/books?id=nlth_e_nVSQC&;pg=PA102&lpg=PA102&dq=Mariegola+of +mask+makers&source=bl&ots=iWMmOsmWLW&sig=2Ial4I1XNwXg6GeJU1uPnxuvlEs&hl=en&sa=X&ei=knzYUaeMComG9gTmzIG4DA&ved=0CGYQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q=Marie gola%20of%20mask%20makers&f=false Date accessed: 16 September 2013

"Daventry Mask, The". Approx 1500-1600 AD. Portable Antiquities Schema. The British Museum. http://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/402520. Date accessed: 16 September 2013. (item not on display to public. Accessible online.)

De Bruyn, Abraham. Omnium Poene Gentium Habitus. 1581. Fashioning the Early Modern Era. http://www.fashioningtheearlymodern.ac.uk/object-in-focus/visard-mask/ Date accessed: 16 September 2013.

"Herbal of Dioscorides Pedanius" Schoenberg Collection. Web 12 Dec. 2012. http://sceti.library.upenn.edu/sceti/ljs/PageLevel/index.cfm?option=view&;ManID=ljs062

"Lady Clapham's Doll Mask." Approx 1690. Victoria and Albery Museum. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O82639/dolls-mask-unknown/ Date accessed: 16 September 2013. (item not on display accessible online)

Maginnis, Tara, PHd. "A muslin mache mask." Costumer's Manifesto. http://www.costumes.org/advice/costcraftsmanual/tmpjk2.htm Date acceessed: 16 September, 2013

"Mascareri exhibit." Salisbury University. http://www.salisbury.edu/newsevents/fullstoryview.asp?id=3670 Date accessed: 16, September 2013

"Masked art." http://www.maskedart.com/pages/venetian-masks-tradition Date accessed: 16, September 2013.

Mazzaoui, Maureen. The Italian cotton industry in the later middle ages. 1100-1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Mellini, Domenico. Le dieci mascherate delle bvfole mandate in Firenze il giorno di carnouale l'anno 1565. : con la descrizzione di tutta la pompa delle maschere, e loro inuenzioni. The Getty Research Institute. http://archive.org/details/lediecimascherat00mell. Date accessed: 16 September 2013.

"Paperwright." Trytel Papermaking. Web. 23 Dec. 2012. http://users.trytel.com/~brittq/mould.htm. Date accessed: 16 September 2013

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Online. Project Gutenburg: http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/readfile?fk_files=1451950. Date accessed: 16 September, 2013.

Ruthvene, Violet (SCA). "An introduction to masks in 16 century Venice, Italy." Trystan's Costume Closet. http://trystancraft.com/costume/2010/02/05/an-introduction-to-masks-in- 16th-century-venice-italy/. Date accessed: 16 September 2013

"Spread of Papermaking in Europe." Georgia Technological Institute. Last updated: 13 Jan. 2006. Date accessed: 23 Dec. 2012. | | http://www.ipst.gatech.edu/amp/collection/museum_pm_euro.htm

Tieuli, Michel. "A short history of Venetian carnival masks." Venice Mask Shops, Ltd. http://www.venetianmasksshop.com/history.htm. Date accessed 16 September 2013.

Twycross, Meg. Sarah Carpenter. Masks and Masking in Medieval and Early Tudor England. Medieval Academy of America. Vol 79, number 4. Oct 2004.

Date accessed 16 September 2013

"Venetian Carnivale Masks" Venezia.net, 2011. http://en.venezia.net/venetian-carnival- masks.html Date accessed: 16 September 2013.

"Venetian Masks." Venice and its lagoons: World Heritage. http://www.venicethefuture.com/schede/uk/232?aliusid=232 Date accessed: 16 September 2013

'Viol - Vizard mask', Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1550-1820 (2007). http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=58907 Date accessed: 16 September 2013.

"Vizards and Invisories: Ladies' masks in the 16th and 17th centuries." Medieval and Renaissance Material Culture. http://www.larsdatter.com/vizard.htm Date accessed: 16 September 2013.

Watt, Melinda. "Renaissance Velvet Textiles". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/velv/hd_velv.htm (August 2011). Date Accessed: 17 September 2013.

http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/20463147?uid=3739600&;uid=2&uid=4&uid=3739256&sid=21102663913821

------

Copyright 2014 by Lana Tessler. <minxlette at gmail.com>. Permission is granted for republication in SCA-related publications, provided the author is credited. Addresses change, but a reasonable attempt should be made to ensure that the author is notified of the publication and if possible receives a copy.

If this article is reprinted in a publication, please place a notice in the publication that you found this article in the Florilegium. I would also appreciate an email to myself, so that I can track which articles are being reprinted. Thanks. -Stefan.

<the end>