This document is also available in: text or Word formats.

Old-Icelandic-art - 6/23/11

"The Old-Icelandic Manuscripts: An Overview" by Baron Fridrikr Tomasson

NOTE: See also the files: Iceland-msg, Iceland-bib, fd-Iceland-msg, alphabets-msg, calligraphy-msg, Paleo-Scribes-art, parchment-msg, inks-msg.

************************************************************************

NOTICE -

This article was submitted to me by the author for inclusion in this set of files, called Stefan's Florilegium.

These files are available on the Internet at: http://www.florilegium.org

Copyright to the contents of this file remains with the author or translator.

While the author will likely give permission for this work to be reprinted in SCA type publications, please check with the author first or check for any permissions granted at the end of this file.

Thank you,

Mark S. Harris...AKA:..Stefan li Rous

stefan at florilegium.org

************************************************************************

The Old-Icelandic Manuscripts:

An Overview

Presented by Baron Fridrikr Tomasson

Æthelmearc Heralds & Scribes Symposium

2 Aprille AS 45 (c.e. 2011)

In the early twelfth century (about

1123), about a century after Christianity (and with it, writing of records) was

introduced into Iceland, the first history of the Icelandic settlers, the Íslendingabók, by Ari Þorgilsson, was

written. It was followed, over the next four centuries, by many manuscripts of

a variety of histories, sagas, and treatises, including books of the

laws proclaimed at the various Þings.

Among these manuscripts were a series of manuscripts which recorded the

so-called Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson.

Also included among these manuscripts were the poems which make up the Poetic Edda, a collection of the

earliest myths of the Germanic and Norse people. [[1]]

The most important manuscripts of the Old Norse-Icelandic period are currently held in a number of Scandinavian institutions, most significantly the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, located in Reykjavik, Iceland and Copenhagen, Denmark. [[2]] This collection is the source for almost all of the digital images used in this paper and the accompanying PowerPoint presentation.

In this paper, I will give a brief overview of the history of the Old Icelandic manuscripts and a discussion of three or four of the manuscripts held by the Árni Magnússon Institute. I will also present a brief analysis of the hand used in the mss, as well as an explanation of several of the abbreviations which are common in the mss. I hope that this paper and class will lead to more authentic scrolls to the medieval Icelandic period being made by scribes.

A Brief History of Old Icelandic MSS

According to the Árni Magnússon Institute, the first manuscripts produced in Icelandic were primarily religious text or laws, dating to the late 11th - early 12th centuries. Production of vellum manuscripts continued through about 1450-1500. After that date, most MSS are on paper rather than vellum. We will focus only on vellum MSS during this class.

The oldest fragments of Icelandic manuscripts that have survived were written in about the year 1200, or shortly before. Their texts are about Christian doctrine and secular laws. Laws were first written down in about 1120, and at about the same time, Ari the Learned wrote his Íslendingabók (Book of the Icelanders), describing the country's governmental structure and history from the settlement down to his own day. It is likely that the first version of Landnámabók (the Book of Settlements) was compiled round about the same date. The oldest Icelandic law code is called Grágás (Grey Goose) is preserved in two vellum manuscripts written shortly after 1250. [[3]]

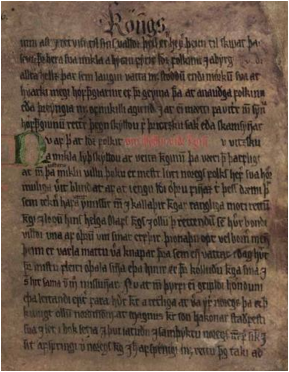

Grágás is contained in the Jónsbók (AM 334 fol) which dates to 1260-1280. It is well-preserved and fairly legible (see Appendix A for two facsimile pages). Along with AM 334, we will be looking at four other MSS from the Árni Magnússon Institute’s collection: GKS 2365 4to which dates from 1260 to 1280 and contains poems from the Poetic Edda: GKS 2367 4to which dates from 1300-1350 and contains Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda; GKS 3268 4to and GKS 3270 4to, dated to late 13th century, containing copies of the laws; among other works (see Appendices B, C, and D for facsimile pages). Other famous MSS from the medieval time period in Iceland are the Flateyjarbók (GKS 1005), dated to 1387-1394, containing many Kings’ Sagas; Möðruvallabók (AM 132), dated to 1440-1460, which contains the Íslendingasögur (Sagas of Icelanders), containing many of the so-called Family Sagas; and, AM 350 fol dated to about 1363, containing Lög, Kristinréttur Árna biskups o.fl. (Laws and a book of stories about the bishops of Iceland)[[4]]

GKS 2365 4to

This manuscript, part of the Codex Regius, was probably produced in the south of Iceland, circa 1270. It is usually paired with GKS 2367 4to. GKS 2365 4to contains twenty-nine Norse poems including the Voluspa, Rísþula, Vọlundarkviða, Lokasenna, and Skirnismal, and other mythological poems from the Poetic Edda; and the Atlakviða, Atlamál in grœnlenzko, Guðrúnarhvọt, and Hamðismál, among other heroic poems from the Poetic Edda. [[5]] The Codex Regius is the primary source for the Poetic Edda.

One comment on the layout of GKS 2365, GKS 2367, and most other manuscripts that present poetry: poetry is lined out exactly as prose is. This makes it difficult to locate the poetry in the manuscripts. I believe this was done to save vellum and it does present an interesting option for the scribe.

GKS 2367 4to

Again, this manuscript was written in the south of Iceland, between 1300 and 1325. Its provenance indicates that it was probably written by a member of the household of Oddi Þorgilsson and passed down through the family until it was copied over in the 17th century. GKS 2367 4to contains all of the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: the Prologue, Gylfaginning, Skálskaparmál, Þulur, and Háttatal; and two skaldic poems: the Jómsvíkingdrápa and Málsháttakvædi. [[6]] Again, because it is one of the primary sources for Snorri’s Edda, the Codex Regius is one of the most significant of the extant manuscripts. [[7]]

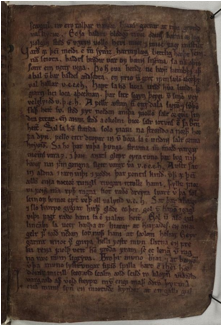

GKS 3268 4to and GKS 3270 4to

These two manuscripts present the Jónsbók, the manuscripts of the Norwegian law presented to the Icelanders after they submitted to him in 1262-1264 [[8]]. Along with the Konungsbók (GKS 1157 4to, dating from 1240-1260) and the Staðarhólsbók of Grágás (AM 334 fol, dating from 1260-1281), GKS 3268 and GKS 3270 represent the primary sources for the laws that ruled the Commonwealth of Iceland in period. These manuscripts date to 1340-1360. [[9]]

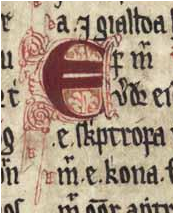

What is interesting in GKS 3268 and GKS 3270 is the layout (two columns), the more formal hand, and the elegant, yet simple capitals used to mark the openings of sections of the laws.

Applying Old Icelandic MSS to SCA scrolls

In looking at using the styles of Old Icelandic manuscripts to the SCA, I would note the following ideas. Please bear in mind that I am certainly not a scribe, nor am I in any way claiming to be an expert of any sort in the scribal arts. However, I think that looking at Old Icelandic manuscripts can certainly add to the range and scope of the scrolls that are produced, allowing Old Norse - Old Icelandic personæ to receive scrolls that are suited to their personæ. With that in mind, I want to look at three areas: the hand being used, the abbreviations being used, and the capitals being used.

The scribes who calligraphed these manuscripts display some idiosyncrasies, especially in the abbreviations they used. The hands differ widely from manuscript to manuscript. The wildest hand I have seen is used in AM 432 12mo (Mágretr saga, dated to 1400-1450). The most elegant hands are in GKS 3268 and GKS 3270. Given the varieties of hands and their similarities, I believe that the closest hand to the Old Icelandic manuscripts is the English proto-gothic charter hand. [[10]]

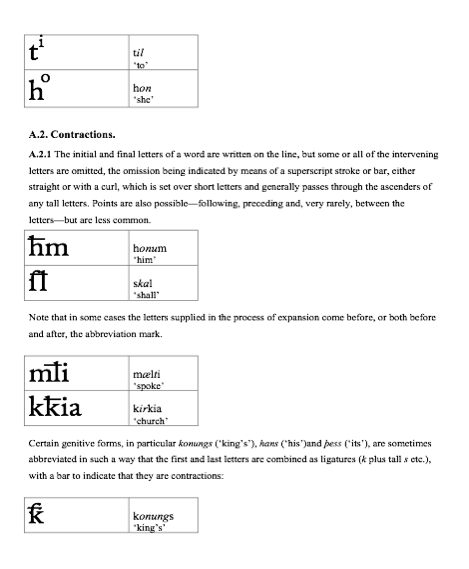

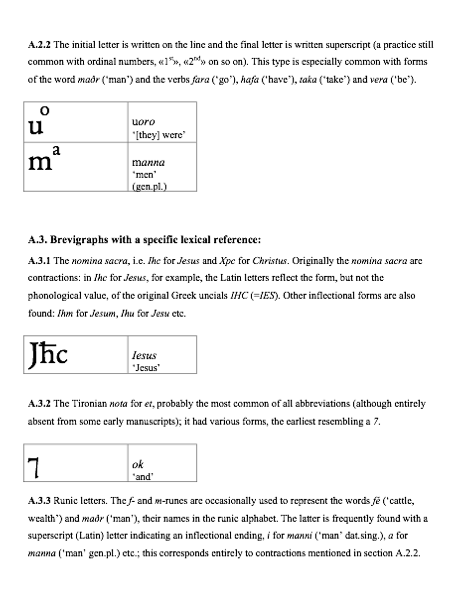

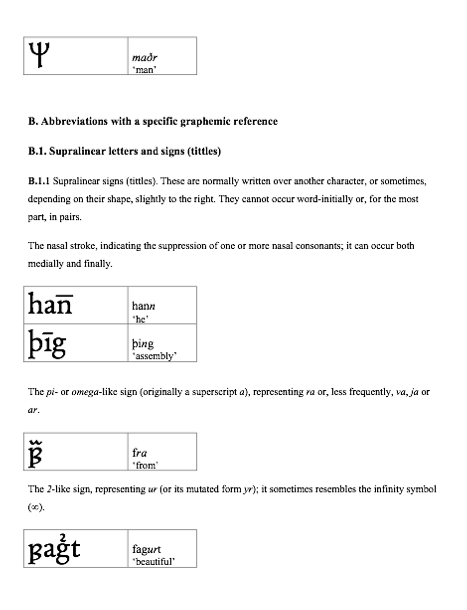

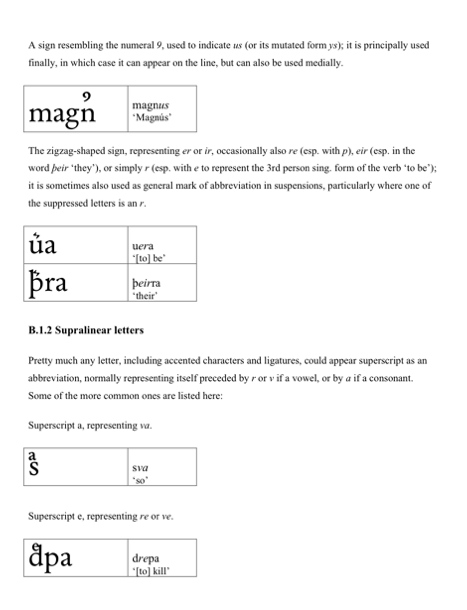

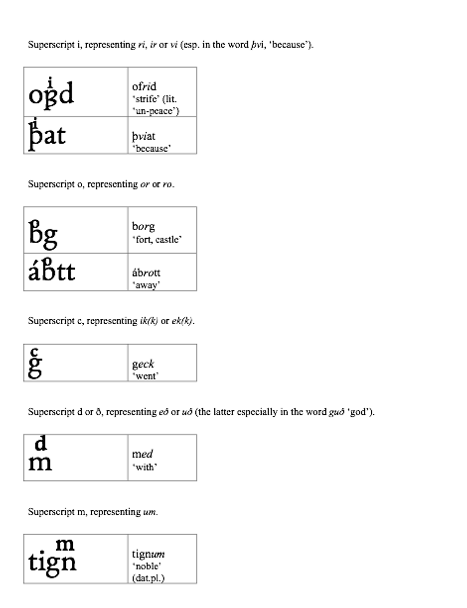

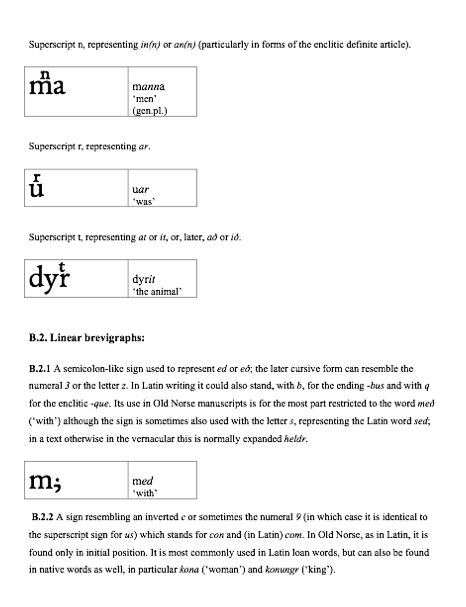

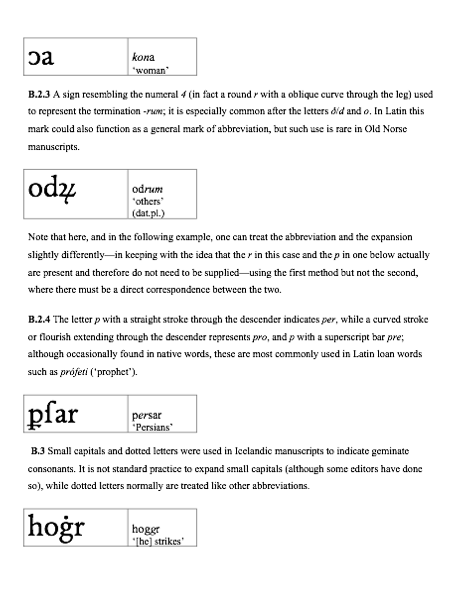

As is common in most proto-gothic and gothic manuscripts, Old Icelandic manuscripts use abbreviations for the most common words (such as Konung, “king”) and dipthongs and other letter combinations. An excellent study of these has been made by Dr. Matthew Driscoll at the Árni Magnússon Institute. [[11]] I have appended his list of abbreviations in Appendix E. If a scribe wants to create a document in a truly authentic Old Icelandic hand, these abbreviations should be a worthwhile tool.

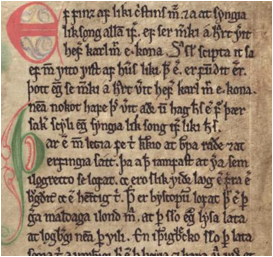

Finally, I want go look at the illuminated initials, capitals, and rubrics that are used in Old Icelandic manuscripts. The primary purpose of the illuminated capitals is to mark the beginnings of main sections of a manuscript. At least in the laws manuscripts, these are sometimes accompanied by true rubrics (red lettering) to mark the section breaks. I have noted that many of the illuminated capitals and initials are drawn to fill the margins, often featuring extended ascenders and descenders, especially on thorns (Þ).

Conclusion

In writing this paper, I have attempted to introduce an early-period manuscript style, with background on the history and contents of these manuscripts. It is my hope that this paper and the class it accompanies will inspire scribes to attempt this style in their future scrolls.

Footnotes

[1] For the Prose Edda, see Byock 2005; for the Poetic Edda, see Larrington 2008; for the Laws (Grágás), see Dennis 2000 and Dennis 2006.

[2] For a list of the MSS held by the Arnamagnean Institute, see Handrit.Is

[3] Árni Magnússon Institute 2008.

[4] Ibid. To see a complete list of the facsimiles that the Árni Magnússon Institute has out on-line, see Stafrænt handritasafn.

[5] Dronke 1969, p. xi; Dronke 1997, p. xi.

[6] Nordal, pp 30, 6-47.

[7] Árni Magnússon Institute, “Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda (GKS 2365 4to)”

[8] Dennis 2006, p. 16.

[9] Handrit.is has great details on the manuscripts held by the Árni Magnússon Institute, if you can read Icelandic. Even with the language barrier, Handrit.is is very useful source, especially when used in concert with Stafrent handritasafn.

[10] Tillotson ≪http://medievalwriting.50megs.com/writing.htm

[11] Driscoll 2008. I want to publicly thank Dr. Driscoll for providing this material and giving e permission to use it in this paper.

[12] All images shown in Appendices A-D are from Stafrænt handritasafn.

[13] Driscoll 2008, pp. 4-11. reproduced permission of Dr. Matthew J. Driscoll.

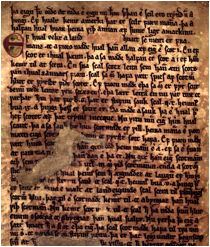

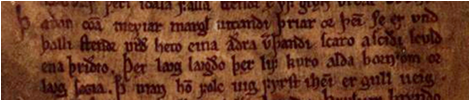

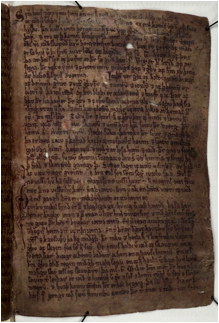

Appendix A: AM 334 fol. [[12]]

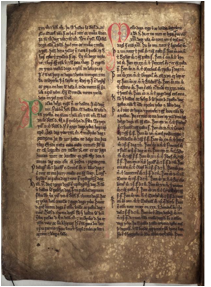

Appendix B: GKS 2365

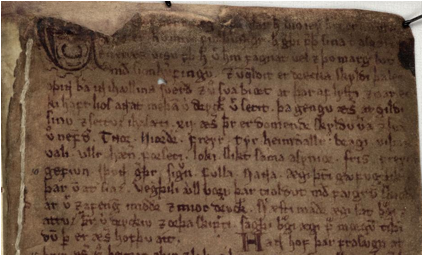

Appendix C: GKS 2367

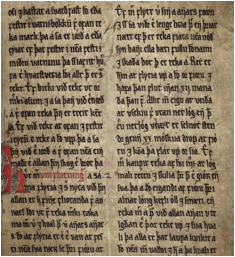

Appendix D: GKS 3270 4to & Initials

Appendix E: Common Abbreviations use in Old Icelandic manuscripts: [[13]]

WORKS CITED

Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies. “Coex Regius of the Poetic Edda (GKS 2365 4to)” Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, 2005. ≪http://www3.hi.is/pub/sam/codex.html≫. Last accessed: 16 March 2011.

Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies. Handrit.is ≪http://handrit.is/≫ Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, 2006-2011. Last accessed: 12 March 2011.

Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies. “Iceland’s earliest writings and some well-known manuscripts” ≪http://www3.hi.is/pub/sam/manuscripts.html≫ Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, 2008. Last accessed: 12 March 2011.

Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies. Stafrænt handritasafn: List of Digitalized Documents ≪http://www.am.hi.is:8087/≫ Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, 2006-2011. Last ac cessed: 13 March 2011.

Clover, Carole, and John Lindow, eds. Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A Critical Guide, rev. ed. University of Toronto Press, 2005.

Codex Regius of Eddic poems: Völuspá. Medieval Nordic Text Archive. ≪http://gandalf.uib.no:8008/corpus/menota.xml≫ Last accessed: 12 March 2011.

Dennis, Andrew, Peter Foote, and Richard Perkins, ed. Laws of Early Iceland, vol. 1. University of Manitoba Press, 2006.

Dennis, Andrew, Peter Foote, and Richard Perkins, ed. Laws of Early Iceland, vol. 2. University of Manitoba Press, 2000.

Driscoll, Matthew J. “Abbreviations in Old-Norse Icelandic Manuscripts.” Unpublished paper, 2008.

Dronke, Ursula, ed. and trans. The Poetic Edda, vol. 1: Heroic Poems. Oxford University Press, 1969.

Dronke, Ursula, ed. and trans. The Poetic Edda: Vol 2: Mythological Poems. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Karlsson, Stefán. “The Localisation and Dating of Medieval Icelandic Manuscripts.” Saga Book, vol. 25, pp. 138-158. The Viking Society for Northern Research, 1998-2001. ≪http://www.vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Saga-Book%20XXV.pdf≫ Last accessed: 12 March 2011

Larrington, Carole, trans. The Poetic Edda. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Nordal, Guðrún. Tools of Literacy: The Role of Skaldic Verse in Icelandic Textual Culture of the Twelfth and thirteenth Centuries. University of Toronto Press, 2001.

Pálsson, Herman. “Tertium vero datur: A study on the text of DG 11 4to.” ≪http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:322558/FULLTEXT02≫ Last accessed: 12 March 2011.

Snorri Sturluson. The Prose Edda. Ed., Jesse Byock. Penguin Books, 2005.

Sveinsson, Einar Ólaf. Dating the Icelandic Sagas: An Essay in Method. Viking Society for Northern Reasearch, 1958. ≪http://www.vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Text%20Series/Dating%20the%20icelandic%20sagas.pdf≫ Last accessed: 12 March 2011

Tillotson, Diane. Medieval Writing. Dr. Diane Tillotson, 2005. ≪http://medievalwriting.50megs.com/writing.htm≫. Last accessed: 16 March 2011.

Wanner, Kevin J. Snorri Sturluson and the Edda: The Conversion of Cultural Capital in Medieval Scandinavia. University of Toronto Press, 2008.

------

Copyright 2011 by Tom Ireland-Delfs, 731 South Main Street, Newark, NY 14513. <fridrikr at thescorre.org>. Permission is granted for republication in SCA-related publications, provided the author is credited. Addresses change, but a reasonable attempt should be made to ensure that the author is notified of the publication and if possible receives a copy.

If this article is reprinted in a publication, I would appreciate a notice in the publication that you found this article in the Florilegium. I would also appreciate an email to myself, so that I can track which articles are being reprinted. Thanks. -Stefan.

<the end>